A lot has been written about WikiLeaks. Too much perhaps, which is why I’m a little reluctant to add what might seem like an obvious point. But it seems important to me, so here we go:

The real importance of WikiLeaks is that it burst the security clearance bubble.

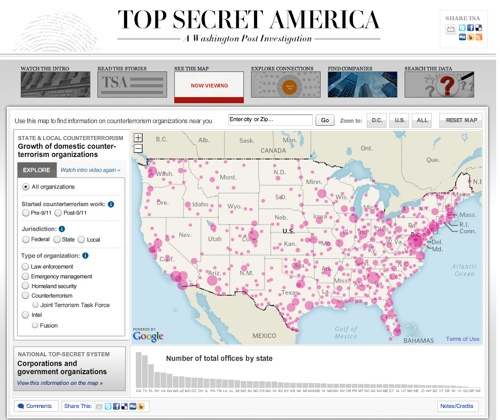

A short time before cablegate happened, the Washington Post ran an important series of articles about “Top Secret America.” Articles which I felt didn’t get the attention they deserved at time. Here are a few key facts:

- An estimated 854,000 people, nearly 1.5 times as many people as live in Washington, D.C., hold top-secret security clearances.

- Analysts who make sense of documents and conversations obtained by foreign and domestic spying share their judgment by publishing 50,000 intelligence reports each year — a volume so large that many are routinely ignored.

- Many security and intelligence agencies do the same work, creating redundancy and waste. For example, 51 federal organizations and military commands, operating in 15 U.S. cities, track the flow of money to and from terrorist networks.

Only a few people have high enough security clearance to be able to see the big picture, but they are so overwhelmed by the amount of data they are exposed to that they can’t make head or tail of it:

In the Department of Defense, where more than two-thirds of the intelligence programs reside, only a handful of senior officials — called Super Users — have the ability to even know about all the department’s activities. But as two of the Super Users indicated in interviews, there is simply no way they can keep up with the nation’s most sensitive work.

“I’m not going to live long enough to be briefed on everything” was how one Super User put it. The other recounted that for his initial briefing, he was escorted into a tiny, dark room, seated at a small table and told he couldn’t take notes. Program after program began flashing on a screen, he said, until he yelled ”Stop!” in frustration.

“I wasn’t remembering any of it,” he said.

As to the value of having such “Super User” status, it is worth looking back at the advice Daniel Ellsberg gave Henry Kissinger when he first came to the White House in 1968:

Over a longer period of time — not too long, but a matter of two or three years — you’ll eventually become aware of the limitations of this information. There is a great deal that it doesn’t tell you, it’s often inaccurate, and it can lead you astray just as much as the New York Times can. But that takes a while to learn.

In the meantime it will have become very hard for you to learn from anybody who doesn’t have these clearances. Because you’ll be thinking as you listen to them: ‘What would this man be telling me if he knew what I know? Would he be giving me the same advice, or would it totally change his predictions and recommendations?’ And that mental exercise is so torturous that after a while you give it up and just stop listening.

What I’d like to argue is that what is important about such high level security clearance is not the information you have access to, but the authority it confers. Just as Louis XIV of France kept a tight leash on the aristocracy by controlling who was allowed to stay with him in Versailles, in today’s government security clearance gives one access and loosing it is is like being banished from court.

WikiLeaks exposed the fact that the emperor has no clothes. Here’s how Umberto Eco put it:

The rule that says secret files must only contain news that is already common knowledge is essential to the dynamic of secret services, and not only in the present century. Go to an esoteric book shop and you’ll find that every book on the shelf (on the Holy Grail, the “mystery” of Rennes-le-Château [a hoax theory concocted to draw tourists to a French town], on the Templars or the Rosicrucians) is a point-by-point rehash of what is already written in older books. And it’s not just because occult authors are averse to doing original research (or don’t know where to look for news about the non-existent), but because those given to the occult only believe what they already know and what corroborates what they’ve already heard. That happens to be Dan Brown’s success formula.

The same goes for secret files. The informant is lazy. So is the head of the secret service (or at least he’s limited — otherwise he could be, what do I know, an editor at Libération): he only regards as true what he recognises. The top-secret dope on Berlusconi that the US embassy in Rome beamed to the Department of State was the same story that had come out in Newsweek the week before.

Umberto Eco suggests, as many others have, that the reason diplomats are upset about the release of these memos is because they expose “a breach of the duty of hypocrisy” by which cordial relations are maintained with our allies. But I think this is wrong. I believe it is precisely because the leaked documents are mostly “common knowledge” that they are most threatening.

Eco’s second point is closer to mine own. He says that “to actually reveal, as WikiLeaks has done, that Hillary Clinton’s secrets were empty secrets amounts to taking away all her power.” But Eco is vague about the mechanism by which such revelations might hurt Clinton. It isn’t just that the cables reveal “empty secrets.” They undermine the the elaborate hierarchy of secrecy as political capital which upon which power structure of Washington DC is based. By exposing the capital of political power—access to classified documents—as essentially worthless, cablegate has burst the security clearance bubble.

UPDATE: Made some changes to the concluding paragraph to better clarify both Eco’s argument and my own.