I’ve struggled with hip pain for twenty years. I mostly kept it under control with regular Iyengar Yoga practice, which I started in 2002, but over time I’ve come to feel that yoga alone isn’t enough. Yoga helped some of my problems, but others continued to get worse. The thing is that to do yoga correctly (and get all the benefits) you need to already be stronger and more flexible in certain muscle groups than I ever was. This means that, despite years of practice with some of the best teachers, and making huge gains in certain areas, there are still many aspects of yoga where I continue to struggle. As a result, I don’t get the full range of benefits that a better practitioner would get, even with all the props and tools used in the Iyengar style.

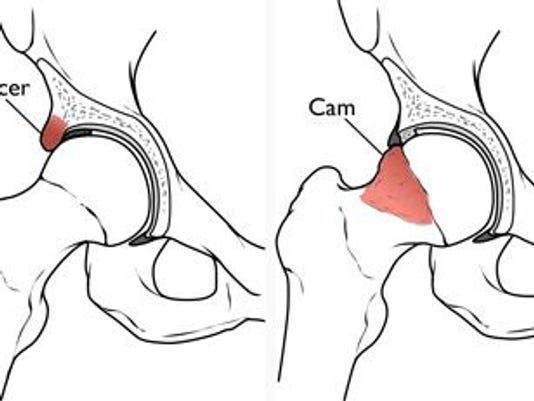

This came to a head last October. For weeks I was being kept up at night by leg pains. I had X-rays, MRIs, CAT scans, blood tests, etc. but nobody could give me a definitive diagnosis. The best I got was Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

[FAI Illustration. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.]

This diagnosis depressed me at first, because it seemed there was little I could do, short of surgery (which only helps some people). In desperation I started exploring YouTube and found that there were actually a lot of physical therapy exercises I could do that might help. After just a few weeks these exercises helped me a lot: reducing my pain, increasing my mobility, and improving my sleep! But I soon reached the limit of what I could do at home, with just my bodyweight. So I decided that I would start going to the gym.

I always hated the gym. I looked down on strength training as boring and not particularly useful for anything other than body building. But now that I had seen for myself how important building basic strength in the stabilizing muscles of the hips had been for my own recovery, I wanted to know more. I turned to the book Which Comes First, Cardio or Weights?: Fitness Myths, Training Truths, and Other Surprising Discoveries from the Science of Exercise by Alex Hutchinson in order to understand what science says about working out at the gym. What follows is summary of what I learned from that book. I’m posting it here because I think a lot of other people could benefit from knowing a few simple things about working out.

This is not meant as medical advice. Anyone with a serious chronic condition should see a trained professional. Also, there are no specific workouts recommended in this book, it is just an overview of the science. Before starting a new workout routine it is a good idea to take classes with a professional trainer.

The body needs stress

Hutchinson says that all forms of exercise are essentially subjecting the body to stress, causing the body to “gradually adapt over time to overcome whatever demands are placed on it.”

The stress could be lifting weights or pedaling a bicycle, and the adaptation is bigger muscle fibers, a stronger heart, and hundreds of other microscopic changes. The key is balancing the size of the stress: too small (lifting a half-pound weight, say), and your body won’t see any need to adapt; too large, and it won’t have a chance to adapt due to injury or exhaustion.

The benefits come from how your body adapts to stress. It does so by becoming more efficient, and these efficiencies are what make us healthier. These affect how we process calories, how we generate mitochondria, how we burn fat, and even how blood flows to the brain, helping memory and cognition as well! Some of these changes happen almost immediately, others kick in over time, but they are truly profound.

Take mitochondria, for instance:

Aerobic exercise increases the number of mitochondria, which are essentially the “cellular power plants” in your muscles that use oxygen to produce energy: the more mitochondria you have, the farther and faster you can run, and the more fat your muscles will burn. . . Studies have found that about six weeks of training will boost mitochondria levels by 50 to 100 percent.

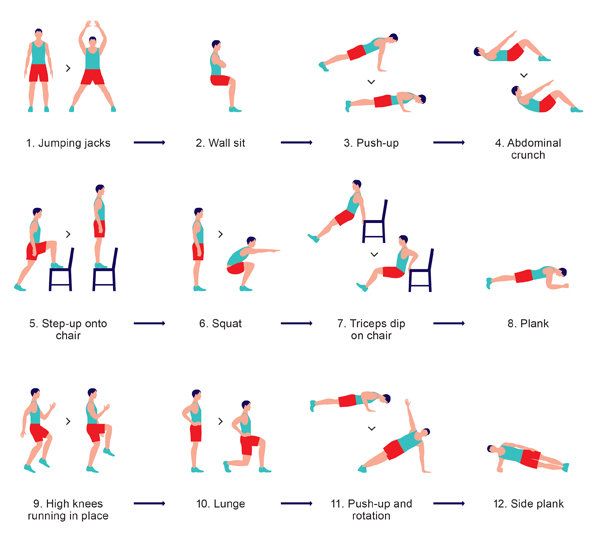

You don’t even need to do a lot of exercise to start getting benefits. Even the famous “seven minute workout” can start bringing about some of these changes.

[Graphic by Ben Wiseman for the NY Times (2013)]

Hutchinson says that more exercise is almost always better:

Those who were just slightly active but didn’t manage to meet the exercise guidelines were 30 percent less likely to die than those who were totally inactive. Stepping it up to moderate exercise reduced risk by only eight more percent, and adding in some vigorous exercise subtracted an additional 12 percent. When you combine that data, you find that getting half an hour of moderate to vigorous exercise five times a week cuts your risk of dying from all causes in half.

And if you are busy, it seems that “you can get away with working out fewer times per week, and with doing shorter workouts—as long as you maintain or even increase the intensity.”

How to do Aerobic Right

One thing the book makes abundantly clear is that you need both strength training and aerobic exercise.

The adaptations that result from aerobic exercise—strengthening the heart, increasing the number of small arteries that circulate blood, stimulating the growth of power-producing mitochondria in your muscles—are quite different from the adaptations produced by strength training. Building strength is primarily the result of two things: increasing the size of your muscle fibers and improving neural pathways so that commands from your brain are executed more efficiently. Both types of exercise are important, but neither is enough on its own.

But you don’t need to go crazy. “You can fit it in by doing a 10- to 15-minute stint on a cardio machine after lifting weights, by playing sports, or by setting aside a couple of workouts a week to focus on cardio.” The important thing is to do it correctly. That means, you need to create the right kinds of stress on your body.

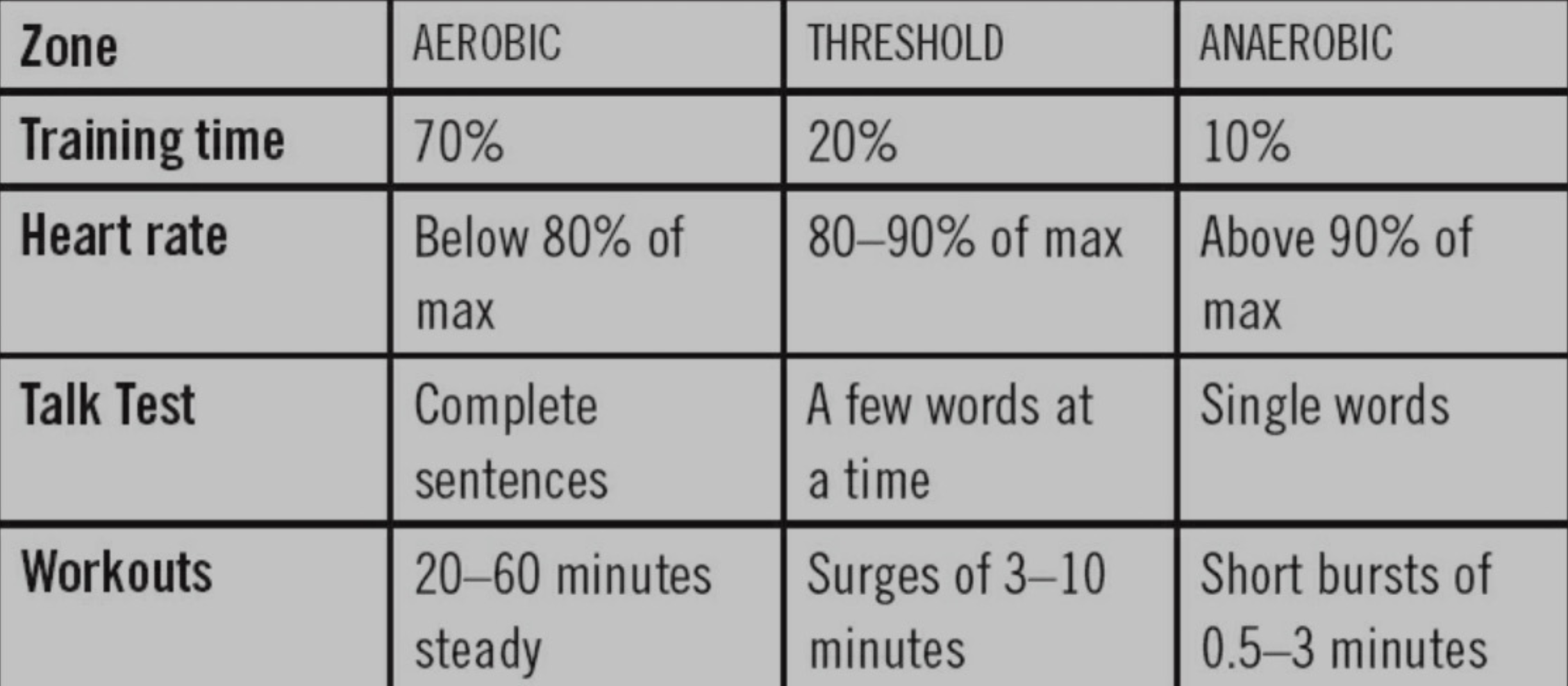

For aerobic exercise, you can divide efforts into three basic zones on the basis of how your body reacts. The easiest is the aerobic zone, where your heart and lungs are able to deliver enough oxygen to your muscles to keep them functioning. In contrast, the hardest, or anaerobic, zone is where your muscles can’t get enough oxygen. In between is the threshold zone, which is marked by a rapid accumulation of lactate in your blood as your muscles begin to cope with insufficient oxygen

The average person should divide their weekly workout (or each individual workout) between these as follows: “70 percent aerobic, 20 percent threshold, and 10 percent anaerobic.” While you can get an Apple Watch or other device to tell you how much to work out, it seems that going by your gut feeling can be nearly as accurate. He discusses this in depth in the book, but I liked what he called the “talk test” the best:

If you’re able to speak in full sentences—out loud, not under your breath—you’re in the aerobic zone. Once you hit the threshold, you’ll start to breathe much harder and only be able to speak in short phrases. And when you can only gasp out a word or two at a time, you’re in the anaerobic zone.

[Aerobic workout chart from book.]

Strength Training

While aerobic exercise is important to “reduce your risk of cancer, heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and so on.” Strength training isn’t just for looking good.

Muscle is the

primary location for burning fat and taking glucose out of your bloodstream, and the biggest contributor to your resting metabolic rate. As the amount of muscle in your body shrinks, you burn fewer calories and your ability to metabolize food gets worse, leaving you more vulnerable to obesity, diabetes, and other conditions.

Studies suggest that “strength training helps people with diabetes regulate their glucose and insulin levels, in some cases more effectively than aerobic training.” And of course I think most people now understand that “strength training also plays a key role in maintaining strong bones.” Not only is muscle important for regulating your body, as you get older, you need to do more to keep the muscle that you have. Hutchinson explains that, “Starting in your 30s, you can expect to lose as much as 1 to 2 percent of your muscle mass each year for the rest of your life.”

Some people are worried about getting huge from weight lifting, but it is actually really hard to bulk up like that. At least for most people. Also, you can work out smart by doing “more repetitions using lighter weights and taking less rest” rather than just doing a few reps with really heavy weights.

How much weight should you use? “whatever weight you use, you should be unable to lift it again when you complete the set.” It seems that many people at the gym (especially women) don’t head this rule and don’t lift enough weight to get the benefits of strength training.

If you plan three sets of 10 reps and you successfully complete them, increase the weight slightly next time so that you’re unable to complete the final one or two reps. New research by Stuart Phillips at McMaster University suggests that reaching failure is the most important factor in building muscle—even more important than how heavy the weights are or how many reps you do. His study found that volunteers lifting at 30 percent 1RM synthesized just as much muscle protein as volunteers lifting at 90 percent 1RM, as long as they lifted to failure.

The book goes into details about working on building power (like you would need for various sports) vs. strength, free weights vs. machines, avoiding injury, diet, dealing with injuries, etc. I won’t go into all that here, but there are four things I want to add.

First, strength training is great for anyone dealing with long term chronic pain. “Those lifting four days a week decreased pain by 28 percent, compared with 18 percent for three days a week and 14 percent for two days a week.”

Second, if you aren’t a professional body builder, you probably don’t need protein powder.

there is reasonable evidence that 1.1 g/kg [of protein] is appropriate for serious endurance athletes and 1.3 g/kg for serious strength athletes. (One g/kg is equivalent to about 1.6 ounces of protein for each 100 pounds of body weight.) Even those amounts are below the 1.6 g/kg that average North Americans tend to eat daily when their diet is unrestricted, Tarnopolsky says. That means an ordinary, balanced diet should easily meet your needs—unless you’re restricting calories to lose weight.

But it is good to get some of that protein “within about an hour of finishing your workout.”

Third, warming up with a “gentle jog” (or dynamic stretches) is better than doing static stretches before a workout. Doing that can actually increase your risk of injury.

And finally, “For the average person working out at the gym for an hour or less at a time, there’s no need to drink anything other than water.” In other words, don’t bother with sports drinks.

Conclusion

I’ve been taking classes from a trainer who has shown me how to use the equipment properly and helped me come up with a routine that matches my own fitness goals. I also continue to do yoga. Basically, I try to do something every day, but vary my workouts so as not to overdo any particular exercise. I alternate between focusing on strength, cardio, and yoga. At least one day a week I do some more “gentle” yoga to help my muscles recover.

I think the most important thing is to find a routine that you can keep up even when you’re busy. It is easier to build new habits on vacation, and my goal now is to try to keep this up during the school year. The book suggests that if you are traveling or busy it is better to do something than nothing. Even a 7 minute workout is a lot better than doing nothing. I feel so much better now than I did a year ago, so I’m pretty motivated to keep to my routine.